Richard M. Biery

M.D., MSPH

The BroadBaker Group, Kansas City, MO

I. INTRODUCTION

Careful thinking requires careful use of language. This article is an exercise in carefully understanding and using the language of belief. Correctly understanding the nature of belief is vital to good soteriology and theology, because the doctrine of salvation by faith apart from works has so often been challenged by redefining faith to include doing good works.1 Hence, this paper will explain and defend a Free Grace approach to belief.2

II. AVOIDING THE DANGERS OF SLOPPY THINKING CONCERNING BELIEF

Generally, a proposition is an assertion about something, and the context normally will tell us whether the speaker intends it as a truth statement or a hypothetical one. As used here, a proposition is an assertion that something is true or that it conforms to reality.

Both Biblically and in the vernacular, to believe is to be convinced or persuaded that a proposition is true. There is no difference between believing something in the Biblical sense and believing something in the secular sense.3 We believe propositions, and our belief system is fundamentally propositional.4

Belief is classed as a mental event that produces a new state of mind, perspective, or attitude toward the proposition as to its truth.5 It is not a decision, but something different than a decision6 and, therefore, neither is it an “act of the will.”7 In neuroscience studies, the “aha” of a new belief occurs in a different part of the brain than decision activity.8 We cannot, by will, decide to believe things we are not convinced are true or know are not true. We can, however, change our willingness to believe it. This is an important difference.

Also, since we become aware of it as having happened in our thinking, (i.e., our state of opinion has changed), and not the result of a willful decision, we perceive it as a passive mental event. We use expressions such as “the light went on,” or “I saw the light,” to try to express our experience of realizing that we have come to believe that something is true. This realization or recognition may occur immediately upon seeing and believing. Or we may realize that we have come to believe something upon later reflection.9

Other terms we (and the Bible) occasionally use for believing are accept and receive. For example, we say, “I accept that,” meaning precisely that we believe it. We don’t commonly use receive in that way, but John 1:12 uses it to mean believe (in Jesus Christ). Fortunately, John goes on and defines it in the same verse to leave no doubt about his use. John defines receive as believe.10

The risk with using accept and receive as synonyms for belief is that they have other definitions which can be illegitimately imported into our definition of faith in order to prove that believing is a decision, willful act, or even a commitment. For example, someone might reason that accepting something is like taking a gift. And since taking a gift clearly involves an action of our will to accept the gift being offered, and if accepting is a synonym for believing, then believing must also involve the will. This form of argument commits the fallacy of equivocation by confusing two different definitions of the word accept (as a synonym for faith or as a conscious action).

In its simplest meaning as translated in the Bible, the term faith is generally used as the noun form of believing.11 But faith in English can also be nuanced to mean something more. Thus, it is open to equivocation. So for now, we will stick to belief as the noun form of believing something.

Expressed in the obverse, belief is freedom from doubt concerning a specific proposition. If we doubt, then we do not have confidence that the proposition is true. The two states of doubt and confidence are mutually exclusive. Rather, a different proposition is believed expressing some level of uncertainty. Doubt and belief regarding the same proposition are mutually exclusive and cannot logically be held simultaneously.

Doubt about a proposition means that a different proposition is actually believed. For example, if you doubt the proposition the Earth is 6000 years old, you may actually believe a different proposition such as the Earth is older than 6000 years, or the Earth is probably billions of years old, or the Earth is probably not 6000 years old. Doubting a proposition means moving from one proposition to believing another. If a new proposition is believed it is clear that one doubts the original proposition and does not have confidence in it.

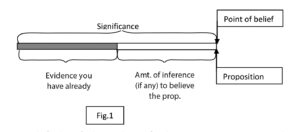

A. Belief Has Both a Scope and Size Component, as Well as a significance

The size component of belief involves an inference, small or large, from where the evidence leaves off and the proposition’s truth is believed. It is the span of the amount of remaining unsupported belief (or faith) between where the evidence, as we perceive it, takes us and the proposition is believed to be true. The amount of evidence needed to believe the proposition is not the same for every person (see figure 1).

It is difficult to find a good term for this intuitive or instant mental acceptance from evidence to belief, since the belief itself is in the final proposition. Some call this the “faith” component. This is fine as long as meanings are clear. However, this usage can lead to a wrong idea of faith. If faith is the noun form of believe, we would simply mean, “I have faith the proposition is true.”

A Biblical example would be Abraham. He believed God’s promise to give him many descendants, including the Messiah.12 He later also believed God concerning the resurrection of his son if sacrificed.13 These are two dramatically different propositions that carry vastly different emotional consequences for Abraham. It is likely that Abraham believed the first proposition more easily (and was justified), but took several years of experience with God to be able to believe and act upon the second.

Different propositions have different levels of significance for us.

Some propositions have little significance for us, such as a news story about a minor incident in a distant country. Nevertheless, if the event seems highly improbable we may still doubt it and therefore not believe it. This would involve a small significance but a large inference.

Some propositions have moderate significance for us, such as believing that one type of dish detergent is better than another. In that case we may require a higher degree of evidence to believe it.

Lastly, some propositions have major significance for us, as when a belief can possibly affect our life such as trusting that an airplane will take us to Malaysia without crashing in the ocean. Another example would be a proposition that impacts our economic well-being.

An additional observation should be made here. We cannot always forecast how much evidence it will take to result in our believing! We learn about or observe evidence, and then, viola!, we become convinced. We start reading something and a few sentences of content may “tip” us into believing. The amount of evidence required to tip us probably depends to some degree on our attitude and temperament (and our reliance, of course, on the testimony and/or evidence). Are we open? Are we normally skeptical? As discussed later, our attitude toward the proposition greatly affects the amount of evidence we require. We may even volitionally reject evidence contrary to what we want to believe or continue believing (an aspect of a cognitive bias called the confirmation bias).

The size of the belief required and the significance it has for us are independent of each other. We may, in fact, have to infer further to believe something of little consequence because the evidence is weak or we distrust it, then we have to infer to believe something of great import but with a great deal of supporting evidence. That is why millions of people get on airplanes every day (and some get on in spite of their doubts).

B. The Strength of Belief

Occasionally, one will read that strength is an aspect of believing. “How strong is your belief?,” we might ask. When it comes to belief, the Bible (particularly the Book of John, which focuses on saving belief) knows nothing of strength” in this way.14 One either believes a proposition or not.

We develop the idea that beliefs come in degrees of strength because people often characterize their believing—say in the supernatural, or in UFOs—as believing it strongly or weakly. They might say, “I mostly agree with you, but…” What they are actually revealing is that they do not believe the proposition in question, but actually believe a different, lesser, or weaker, proposition. For example, instead of believing the proposition, “The supernatural exists,” they are stating that they believe a different proposition, such as, “The supernatural may exist.”

Much more consequential and serious is the fact that if one introduces the idea of strength into Biblical belief in Jesus Christ for eternal life, one has introduced a profound theological (and philosophical) problem. Biblical belief is treated as bivalent. Does it exist or not? However, the notion of strength turns belief into a sliding scale from weak to strong. And if beliefs can be weaker or stronger, this obscures the condition of salvation. For even if we believe the only condition of eternal salvation is faith, if faith comes in degrees of strength we will wonder, “Was our belief strong enough?” And therefore, “How likely is it that we are truly saved?”

A careful reading of the book of John reveals no such concept as strength regarding saving belief in Jesus Christ. John is very consistent. People believed or they did not. One does not see such an idea as intellectual faith or spurious belief.15

Another factor that may give the impression of strength of belief is compound or complex propositions—propositions with several simpler propositions imbedded and which must be believed. This can result in someone saying, “I mostly believe what you are saying, but…” or “I largely agree with you, but…” This sounds like a strength statement, but what is occurring mentally is the acceptance of most of the subpropositions but not all of them. Therefore, the solution to a better understanding of the person’s belief is to break the proposition into its components and find which of the sub-propositions are not yet believed.

Another way of attempting to introduce the idea of strength into belief is the argument that belief is always probabilistic. This also makes belief into a sliding scale, and falls victim to the Fallacy of the Beard,16 and profoundly undermines assurance.

A continuum, whether of works or of faith, introduces unavoidable and crippling uncertainty into one’s confidence of eternal life. It is more reasonable to argue both logically from God’s character, His love and grace, and generally from Scripture, (even aside from clear salvation passages), that God wants His children to know that they are His. The contrary introduces a grey zone into assurance. This seems illogical, even incoherent, given our view of God’s love and grace (see for example John 20:31 and 1 John 5:13). Furthermore, the saving proposition is extremely simple and uncomplicated, indeed the simplest possible. Uncertainty of one’s status is not part of either Jesus Christ’s rhetoric or of the gospel. The message is consistently one of certainty. What must I do to be saved? Believe.

In other words, because He loves us, God wants His children to know that they are His with all the wonderful consequences of that assurance. Introducing a soteriology of uncertainty of being God’s child undermines all motives, even love! What is actually going on in terms of defining saving belief is that a different proposition is being smuggled in, a proposition of probability. We are not convinced the offer is true, but we believe there is a certain probability of it being true.

C. Belief and the Will

I have noted earlier that belief itself is not an act of the will. However, we can and do exercise our attitude and our will regarding the amount of evidence we permit into our belief system. This, in turn, affects the degree of doubt remaining. Thomas is an example of one requiring a great deal of evidence. At least some of the other disciples accepted simple testimonies, while Thomas required personal (and extensive) evidence (seeing and touching) before he thought his doubts would be conquered.

It is important to note that wanting to believe something is not the same as believing it. However, wanting to believe something is true opens us up to evidence and arguments as to the validity of a proposition, such as the reality of UFOs or that God truly loves us and offers us eternal life.

We continue to seek confirmatory evidence for our beliefs (and avoid or ignore contradictory evidence). If we have purchased a car because we believed it was the right choice of the alternatives, we’ll continue to be alert for further supporting evidence, such as paying closer attention to ads or others who believe as we do, etc. The problem with weak evidence is that it makes us more vulnerable to contrary evidence that may persuade us to believe a different proposition. We believe the proposition but know the weakness of its defendability (which is a different proposition!).

Note again, belief is not an act of the will. But what is subject to will is our management of the evidence allowed into our mind to permit us to become convinced. We can refuse to acknowledge clear evidence that contradicts our belief, either by not seeing it as contrary, and refusing to make the inference. We rationalize contrary evidence in order to handle the cognitive dissonance it would create.

However, all belief is potentially defectable, given sufficient contrary evidence permitted into the belief system (the evidence and the resultant belief in the proposition), for good or bad. Thus, belief, our actions, our attitude, and evidence (or truth) constitute a dynamic “closed loop system,” reinforcing each other.

D. Believing Larger Propositions

Beliefs are interconnected. We build propositions one upon another, creating a propositional hierarchy. Foundational propositions allow us to make inferences to higher propositions, leading to an ever-larger conceptual scope of beliefs. Believing a proposition and having it confirmed acts as evidence for a conceptually larger proposition. At some point we create and/or believe the larger proposition.

For example, we may believe what someone says when he agrees to meet at a certain time and place. We may not be ready to believe the larger proposition that the person is more generally reliable. But after repeated experiences with the person’s behavior we come to believe the higher or larger proposition that the person is reliable or trustworthy— at least as to keeping appointments. Since it is a dependency hierarchy, defecting from a lower proposition (perhaps caused by a person not keeping a promise) causes those above to collapse.

This helps explain a couple of puzzling Bible passages that seem to suggest the individual wants their belief “strengthened.” There are at least two ways of interpreting their request. There is either the desire for more supporting evidence to something already believed, or, more likely, help in believing even greater propositions that are not yet believed.

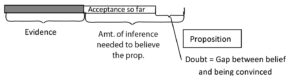

E. Doubt and Worry

Failing to be convinced is doubt. Doubt is the gap between the extent we are inclined to believe versus being finally convinced of the proposition’s truth.

As noted earlier, the degree of doubt can vary. It can be fueled by contradictory evidence, or by refusing to accept the evidence at hand.

Worrying is not the same as doubting. Worrying is being anxious due to doubt. We cannot worry about the truth of our belief without doubt being present.

For example, we can doubt our ability to defend our belief (and worry about it) and still believe the proposition. On the other hand, we can doubt a proposition but not worry about it, particularly if the proposition at stake is of little consequence. Of course, we also can worry in situations not due to doubt at all but due to certainty (e.g., that that there are landmines between us and our objective). The doubt comes in regarding our safety, not our belief.

This writer believes we can manage our worry. This is especially important when we are not in control of the outcome. As noted earlier, doubt is, to some degree, subject to our will via how we handle truth/ evidence. We can make ourselves “open,” teachable, etc., to receive new evidence or not. An example of this is the willful blindness of the Pharisees about Jesus in the face of overwhelming evidence.17 We therefore manage our inclination toward belief by managing the evidence or reasoning that reduces (or increases) our doubts.

III. BELIEF AND THE SOVEREIGNTY OF GOD

Some may ask at this point, “Where is God in this?” How does God influence or draw us to faith? Clearly, according to Scripture, He does so.

God draws us to Himself by revealing truth to our minds. God is in the truth-revealing business because truth (especially Biblical truth) produces belief. The Bible uses the metaphor of light to show that God illumines our minds with truth. God gives truth to the truth-seeker and occasionally, for reasons of His own, seems even to pry a person open to receive His truth. The clearest example of this is perhaps Saul’s encounter with the Lord on the road to Damascus.18 But we remain accountable for our beliefs (and how we handle truth). As noted earlier, belief, truth, and our willingness to be open to the evidence form a system. God interacts within that system to move us towards belief, but without removing our accountability.

IV. BELIEF AND ACTION

How do our beliefs relate to how we act? Many people assume that there is a linear connection between belief and behavior, where one always leads to the other. But reality is more complicated than that relationship suggests.

Belief does not necessarily result in action, but it can. We can act consistently with our beliefs. But we can also act consistently with a proposition that we actually doubt (or we can intentionally be hypocritical). In that case, our action does not mean we believe the proposition, but that we are willing to act in spite of our present state of doubt. When we act upon a proposition we doubt, we are expressing our hope, not our belief. This is a common experience. We often urge people to try something with the hope they will have a confirmatory experience that will result in their believing the proposition. For example, companies will often give out free samples of their products in the hopes you will try it and believe their claims.

The converse of the above is also true. People can be willfully doubtful by refusing to accept or trust evidence and thus to believe. Certain Bible passages suggest this perspective. Jesus non-critically invites Thomas to overcome his doubts (concerning whether Jesus was truly raised to life in the flesh and not some spirit form) and to see additional evidence such as touching the nail and spear marks on His body. This led to what Van Doren calls the greatest confession of Christ in the Scriptures.19 Thomas could have willfully refused to even consider the evidence in order to sustain his disbelief.

It is conceivable and possible that a person may believe a proposition to be true and not act on it. This failure to act may not be related to doubt. We may believe a plane can transport us but it isn’t going where we want. We may trust someone but not want what they offer. Action takes will, and the will to act could be lacking for a variety of reasons such as fear, laziness, selfishness, or emotional cost.

For example, Abraham could have refused to sacrifice Isaac, not because he disbelieved God, but because he was repulsed by it or didn’t want to hurt Isaac. His obedience pursuant to his faith was at stake, not necessarily his belief. When Abraham acted he no doubt demonstrated both his faith and his obedience. By the way, he could have obeyed in spite of doubt. Note again that belief and action are not necessarily dependent on one another. We obey people all the time in spite of our doubt. Motives to obey can involve more than just belief (e.g., such as having a gun at our head).

Since belief-linked action is not required for eternal life,20 actions regarding our Christian faith may follow other propositions. These actions are in the realm, therefore, of obedience or faithfulness. If we believe that love for the brethren is a desire of Christ’s and we decide to act on that belief (enabled by the Holy Spirit), we manifest or demonstrate our belief in that proposition. Otherwise, that belief is dead, un-motivating, or ineffective (though the proposition may yet be believed). Others can’t see it. It doesn’t move us to action. Action in this context takes both motive (another subject) as well as belief. The point of James in his epistle is that faith that is followed with action is confirmed or ratified to others, (or “justified” using James’ language, not Paul’s, since they use the term differently) by the action.21

Some beliefs are not useful until appropriated by action. For example, we may believe in the aforementioned aircraft. The belief is nonproductive until we appropriate the benefit of that belief through getting aboard. Eternal life is not like that. God is the One producing the effect of our belief (i.e., eternal life). The action is His, not ours. Scripture makes that clear over and over.22 Its benefit is effected, or realized, at the time of believing the proposition. John says that the believer has, as a present reality already, eternal life in places like John 3:36 and 5:24.23 Thus, the metaphor of trusting a chair by sitting in it (acting) or trusting to be carried over Niagara Falls by a tight rope walker whom we trust is able to do so by getting on his shoulders (acting) are misleading metaphors and inaccurately represent saving faith.

V. THE SEMANTICS OF BELIEF

In today’s language, the proposition that we “believe someone” versus the one that we “believe in someone” are significantly different propositions.

Believing in a person generally implies we trust him or have faith in him as a consistently reliable person. It forecasts our belief in the person’s future behavior. We come to believe in someone generally because a series of preceding propositions concerning the reliability of the individual have proven true, such as in the case of Abraham regarding God mentioned earlier. Thus we would say, using the terminology here, that believing in someone or trusting them is a higher level, or more complex, proposition. It enfolds conceptually lesser propositions that we additionally believe and often have validated from either our experience or others’ testimony. Thus, the validation of lesser propositions becomes evidence for the larger one.

However, concerning Biblical, and especially Johannine usage, believing “in Jesus” means believing the proposition regarding His Messiahship and that eternal life is the accompanying gift to the believer.24 We only need to look at Jesus’ dialogue with Martha in John 11. He affirms that he is the resurrection and life and that believing in Him results in the same. He then asks her the content of the proposition she believes about Him. She replies that she believes it.

What is the semantic or linguistic relationship between believing, trusting, and faith?

As our usage has suggested above, this depends on how the terms are used. Believing (or belief) is generally the most propositionally precise terms in current English usage. It usually points to a specific proposition, although the proposition may be conceptually either large or small.

Trust and faith are usually used for more complex or higher propositions and could intimate a decision or an act of the will, depending on how they are used. Trusting often, or usually, implies a high order belief (but need not). It is usually in reference to a thing, a person, or a concept (or principle such as scientific law).

We could say, for example, that we are trusting Jones to be on time, meaning we believe he will be on time. However, we tend to use the latter phrase over the former in that more specific construction of a belief. We tend to use trust to indicate a higher order reliance on someone or something (i.e., that they are reliable or trustworthy). Consequently, if someone says they trust Christ, we need to ask, “For what?” in order to establish the accuracy and extent (or significance) of the propositions they believe. Is it for healing? Is it for wealth or needs met? Or is it for their eternal life? Or all three?

Trusting in someone can carry the connotation that we are relying on them (pursuant to our belief in the proposition concerning their reliability). We are depending on them relative to the belief proposition—that they will be on time, or that they will complete the job assigned, and our well-being, to that extent, is dependent on them for that fact. Here, too, the English language permits us to say we can decide to act trustingly (we “trust”) while still having doubt—not total assurance.

In the executive world we use trust this way all the time. For example, we assign a job, not totally convinced of the capacity of a new subordinate. However, their knowing of our trust acts as an incentive that improves their trustworthiness. In English we might also say that we have faith in them or we have put our faith in them.

The tricky aspect surrounding this use of faith and trust for our expression of our action is that our will is involved. We place our dependence on them for something. Note this might be independent of the belief proposition we hold. We could doubt and still assign the responsibility. Believe is therefore the more precise term. Be careful how faith and trust are used and ask for clarity. Note that belief in someone’s reliability concerning something automatically results in our dependence or reliance. There is no act of the will. The results are simply expected as part of the content of our belief. Thus, eternal life is an inherent expected result of believing in Jesus.

In the book of Hebrews we are told that Israel was condemned to wander in the wilderness 40 years because of lack of faith (or trust) in God. They were expected, by the time they reached the land of Palestine from Egypt, to have had sufficient experience with God’s provision to also trust Him to be with them in confronting the enemies waiting for them in the Promised Land. Their fearfulness and timidity was due to lack of belief in the, by then, larger proposition that God would care for them, protect them, and go before them regarding their enemies. They disobeyed because they did not believe or trust God (and consequently perished in the wilderness). In fact, Hebrews 3 explains that their general attitude of distrustfulness led to hardened rejection of even considering evidence to the contrary.

As used today, faith often suggests an even higher conceptual belief proposition. We refer to one’s faith as commonly meaning an entire system of belief propositions. Or we can narrow the meaning to the way trust is used—faith in someone or something, or even more narrowly to mean faith that Jones will be on time. However, we tend not to use it in that manner. Therefore, understanding accurately a reference to one’s faith requires the question, “Faith in what or whom?”

Furthermore, we can say that we believe Jesus heals, and yet not believe He heals in every situation. Thus, we can legitimately situationally doubt (or have uncertainty) while believing in the general proposition. We can trust airplanes in general, but not trust this particular flight, say due to weather, since more is involved in the particular proposition than simply trusting an airplane.

VI. THE DEFECTABILITY OF FAITH

Can belief be abandoned? Absolutely. Belief is defectable. We do it all the time due to new evidence or better reasons to believe something else. A belief, therefore, though genuine at the time, may be fragile or easily abandoned if the size of the inference has been large or the evidence weak. Wrong belief can be difficult to abandon as well and take a large amount of contrary evidence.

John the Baptist appears to have come to doubt his original belief about Jesus Christ while in prison and sought more confirmatory assurance from Him (Matt 11:2). John had such a high view of Jesus in Matt 3:11-14. Now, he questions Him, almost certainly because of his experiences in prison and the fact that there were no signs of the judgment John said Jesus would bring upon the wicked (Matt 3:10).25

When the father of the possessed child said in Mark 9:24, “Lord, I believe; help my unbelief,” he could have meant several things. What is certain is that he did not contradict himself. He may have believed one proposition about Jesus (e.g., His ability to heal) but not believed yet a greater proposition (e.g., His ability to cast out a demon or His Messiahship) and wanted more evidence. Alternatively, he, in fact, could have believed Jesus could heal him but was not certain He would. Or he may have wanted to believe even greater propositions. These are all different propositions. What does seem evident was that he was asking for more assurance (evidence) in support of a proposition he wanted to believe yet did not.26

Defecting from a belief means abandoning one proposition and believing another. For example, as discussed above, an individual may initially believe in a young earth creation (i.e., the Earth is around 6000 years old.). But he may later “defect” from that belief by doubting. Doubting the proposition, the Earth is about 6000 years old, does not mean that he simply believes in nothing. Rather, He believes a different proposition (e.g., the Earth is much more than 6000 years old; or the Earth is probably not 6000 years old; or the Earth is probably billions of years old). The new proposition believed may be a probabilistic one.

Such “migration” of our belief from proposition to proposition is common. The more we expose ourselves to contrary evidence, and not balancing it with supporting evidence, the more a change in our propositional belief is likely. In truth-seeking we must be open to truth, both confirmatory and negative. But Scripture, correctly understood, trumps other forms of evidence.

One more observation needs to be addressed. If the inference required to get from evidence to belief in the proposition is large, and yet we believe it anyway, we may be concerned about our ability to defend that belief. But our confidence (or lack thereof) in our ability to defend our belief is a different proposition than the belief in need of defense. The doubt here is not regarding the belief but the ability to defend it. To mitigate that doubt, we seek supporting arguments and evidence. This will both narrow the belief “gap” (the “inference” presently required) and change the proposition about our ability to defend it. Again, as discussed above, because of the cognitive dissonance humans tend to do this automatically.

VII. CONCLUSION

This article supports the idea that eternal life as offered by Christ depends on belief in the proposition that He grants it to the believer at the point of belief. Scripture, as well as semantic and contextual logic, support the argument that the heavenly consequence is immediate adoption into God’s family (with its attendant eternal life), and that eternal life is truly eternal, and therefore lasting, from the point of belief. It is not dependent on a “committed” belief, on an on-going belief, or a constant renewal of belief in the proposition. As Jesus told the woman at the well, one drink of the living water resulted in a life that would never end. Did she believe that proposition?

____________________

1 For example, while it has been common since the early church to wrongfully add works (Law) to faith for salvation (e.g. Paul’s strong condemnation in Galatians), modern examples include a kind of back door approach that redefines faith by including works. See Zane C. Hodges, The Gospel Under Siege: A Study on Faith and Works (Dallas, TX: Redencion Viva, 1981), 4-6.

2 This article was prompted by remarks made by Dr. Robert Wilkin while discussing saving faith at the 2004 Grace Evangelical Society National Conference. It supports and follows the line of logic and concepts expressed in those remarks.

3 Gordon Clark, Faith and Saving Faith (Jefferson, MD: Trinity Foundation, 1983).

4 A proposition here is a statement regarding a state of being or action, usually for consideration.

5 Webster’s Dictionary, 3rd ed., s.v. “belief.”

6 While Webster calls it a “feeling,” it is also called a “state of mind,” which, I think, is technically a more accurate term because the use of the term “feeling” introduces emotion, a separate event in our mind. Unfortunately the term “state of mind” inadequately describes our conscious cognitive state when we realize we believe something. It is, indeed, close to a feeling, like a light bulb going on or an “aha, I see; I’m convinced.”

7 This paper will elaborate on reasons why belief, as narrowly defined here, is not a decision.

8 Brain activity studies have mapped the phenomenon known as insight, “aha,” realization, discovery, etc., to a complex series of brain states tying it to the right temporal and amygdala, not the frontal lobe.

9 C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life (Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1955), 224. Lewis recounts how he discovered he had come to believe in Jesus Christ on a bus.

10 R. C. H. Lenski, The Interpretation of John’s Gospel (Columbus, OH: Lutheran Book Concern, 1942), 59-63.

11 A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, trans. William F. Arndt and F. Wilbur Gingrich, 4th rev. ed. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1979), 816-18.

12 H. C. Leupold, Exposition of Genesis (Columbus, OH: The Wartburg Press, 1942), 478.

13 F. F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Hebrews, NICNT (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990), 304.

14 All uses of believe in John are free of such modifiers. Mathew 17:20 (mustard seed metaphor) is referring to the size of the proposition to be believed, not the size of the faith. See Bob Wilkin, “Should We Rethink the Idea of Degrees of Faith?,” JOTGES (Autumn 2006): 11-12.

15 Zane C. Hodges, Absolutely Free: A Biblical Reply to Lordship Salvation, Second Edition (Denton, TX: Grace Evangelical Society, 2014), 25-39.

16 See http://www.logicallyfallacious.com. Accessed January 12, 2016. The Fallacy of the Beard involves the question, “How many whiskers does it take to make a beard?” Using this fallacy is an extremely useful test of any soteriology. Simply put, does the means of salvation in the proposed soteriology introduce a continuum as a condition —is it subject to the Fallacy of the Beard by introducing things like repenting, committing, yielding, confessing, strength of faith, endurance, good works, a list of things to believe, etc.? All are subject to the Fallacy and involve profound uncertainty. Many people combine several of these as requirements for salvation, compounding the uncertainty! This causes people to ask how much faith does it take to have faith.

17 H. A. Ironside, Addresses on the Gospel of John (New York, NY: Loizeaux Brothers, Inc., 1954), 411.

18 W. O. Carver, The Acts of the Apostles (Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1916), 92-93.

19 William H. Van Doren, Gospel of John: Expository and Homiletical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1981), 1380.

20 Joseph C. Dillow, The Reign of the Servant Kings (Haysville, NC; Schoettle Publishing Co., 2006), 135.

21 See Thomas Constable’s discussion on James, especially James 2:21, at www. soniclight.com. Accessed Dec 19, 2015.

22 Zane C. Hodges, The Hungry Inherit (Dallas, TX: Redencion Viva, 1997), 134. This is the essence of the Grace message of the free gift of eternal life upon believing in Jesus.

23 Barclay M. Newman and Eugene A. Nida, A Handbook on the Gospel of John (New York, NY: United Bible Societies, 1980), 105, 158.

24 Robert N. Wilkin, “The Gospel According to John,” in The Grace New Testament Commentary (Denton, TX: Grace Evangelical Society, 2010), 476.

25 Craig L. Blomberg, Matthew, The New American Commentary (Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1992), 185.

26 Wilkin, “Degrees of Faith,” 5-7.