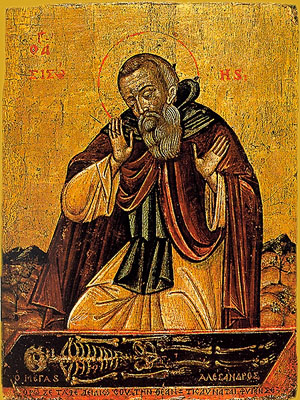

Whenever I hear it said that repentance is a condition of eternal salvation, I think of St. Sisoes the Great (d. 429).

Sisoes was one of the first great monastics—St. Anthony’s successor—who lived deep in the Scetian Desert, in an area known today as Wadi El Natrun. I think of Sisoes because of the story told about his death.

According to the story, as Sisoes lay on his deathbed, surrounded by his disciples, his face began to shine like the sun, and it appeared as if he was talking to someone in a vision. The disciples asked who he was speaking to, and the great monk explained that angels had come for his soul. He was entreating them to tarry just a little while longer so that he might have more time to repent.

This admission shocked the disciples. They revered Sisoes as a holy man who who had lived an angelic life. By subjecting himself to the most extreme forms spiritual introspection, self-deprivation, and both physical and spiritual suffering, he had attained holiness. So they naturally exclaimed: “But you have no need for repentance, Father!”

Sisoes famously replied: “I do not know in my soul if I have even begun to repent.”

This story is told as evidence of Sisoes’ great humility, i.e., the fact that he desired to live a little longer in order to repent proves he was too humble to even recognize his own holiness! And from various other (spurious?) details of the story—including an appearance of Christ Himself who takes Sisoes to heaven, leaving behind a cave filled with a heavenly fragrance—we are supposed recognize that Sisoes truly needed nothing to repent of, that through his arduous efforts, in cooperation with the divine energeia, he had truly achieved theosis (an Orthodox term encapsulating both sanctification and glorification, but with a Platonic twist).

But I take the story very differently.

After we have stripped it of its hagiographical elements—its visions, eerie voices, and mystical lights—what we are left with is a dying man who had spent his whole life trying to work his way into heaven, only to doubt, in his very last moments, whether his best efforts even counted as a worthy beginning.

What it illustrates is the enormity, and ultimate elusiveness of repentance.

It is this enormity and elusiveness that many preachers have failed to understand. Some plainly teach that by the end of our lives, we must have repented of all our sins in order to be saved. Others preach that, in order to be saved, repentance can and must happen all at once, in conjunction with the moment of faith in Christ. Still others, somewhat more alert to what repentance involves, hesitate to demand repentance in order to receive eternal salvation, but nevertheless make it the condition by which we maintain our salvation over the course of our lives. But whether someone teaches that eternal salvation depends on a moment of repentance or a lifetime of repenting, I can only imagine that such preachers do not truly understand what repentance really requires of us.

I suspect that few evangelicals have tried as hard as the ancient Egyptian monastics to repent of their sins. Those monks took their work salvation very seriously. How many of us have fasted for a day, or a month, let alone for decades? How many of us have faithfully tithed, let alone given away everything we own to the poor? How many of us have stood up for Christ in the workplace, let alone be tortured for the faith? How many of us are willing to set aside a moment or two of devotional time each day, let alone discipline our bodies to the point of death in order to drive away our passions and lusts? Has any evangelical tried to work their way into heaven with more determination? Has any took repentance as seriously? I doubt it.

And yet, these same preachers claim we must repent before receiving everlasting life?

I ask you: Can you repent in a moment? Can you repent well enough, deeply enough, sincerely enough, and perfectly enough to warrant entry into heaven?

I don’t think so. The demand for repentance is too great.

The story of Sisoes illustrates why, if repentance was the condition for eternal salvation, no human effort could ever achieve it.

Repentance is the flipside of the positive demand to fulfill the Law. One requires that we cease doing evil; the other, that we only do good. Both must be done perfectly. And no one has ever achieved that, save for Christ Himself. No wonder that Sisoes came to the end of his life unsure of whether he had even begun to repent! It was an impossible demand to fulfill! In his very last moments, he was plagued with uncertainty. Had he done enough? He wasn’t sure. He needed more time!

It is precisely the monstrous uncertainty created by trying to work our way into heaven that is answered by the good news of the gospel. We do not need to live a life of perfect restraint from evil, or perfect performance of good, in order to be saved. The sole condition for receiving everlasting life is faith in Jesus, that is, faith in His promise to give everlasting life to everyone who believes in Him for it (John 3:16, 36; 6:47). The one and only condition is to believe. Jesus did all the work and paid it all so you could have everlasting life as a gift (Eph 2:8-9). Instead of a gospel of doubt, that is a gospel of gracious assurance.